January Newsletter – Fear of Draw-down

Outside of Twitter, when I meet traders / investors, one word that never is much of a talking point is drawdown. One reason is most investors and traders don’t even calculate a NAV styled return matrix to understand where they stand relative to where they were say a month ago or a year ago.

Maintaining performance records gives a deeper understanding of both the strategy strengths and the weaknesses. While we all remember our winners, the losers barely stand any scrutiny. Finally, the question though – is our return from the total investment that has been committed greater or lower than the Index remains unanswered.

Draw-down is a measure of how much one’s equity has fallen from the peak. Assume you had bought a stock at 100 and it went upto 150 and today trades back at 101, while for all practical purposes you are still profitable, if someone asked what the draw-down on the trade is, you will say it’s 32%. For someone without context, this would seem like you are deep under water even though you are actually floating just above.

Draw-down provides perspective when it comes to trading systems that employ leverage. A higher draw-down in historical testing would mean that one needs a higher amount of margin and lower leverage to be able to overcome and sustain trading the strategy through and through.

While drawdowns are painful and may result in an existential crisis for traders, the question is whether investors should be really bothered with it?

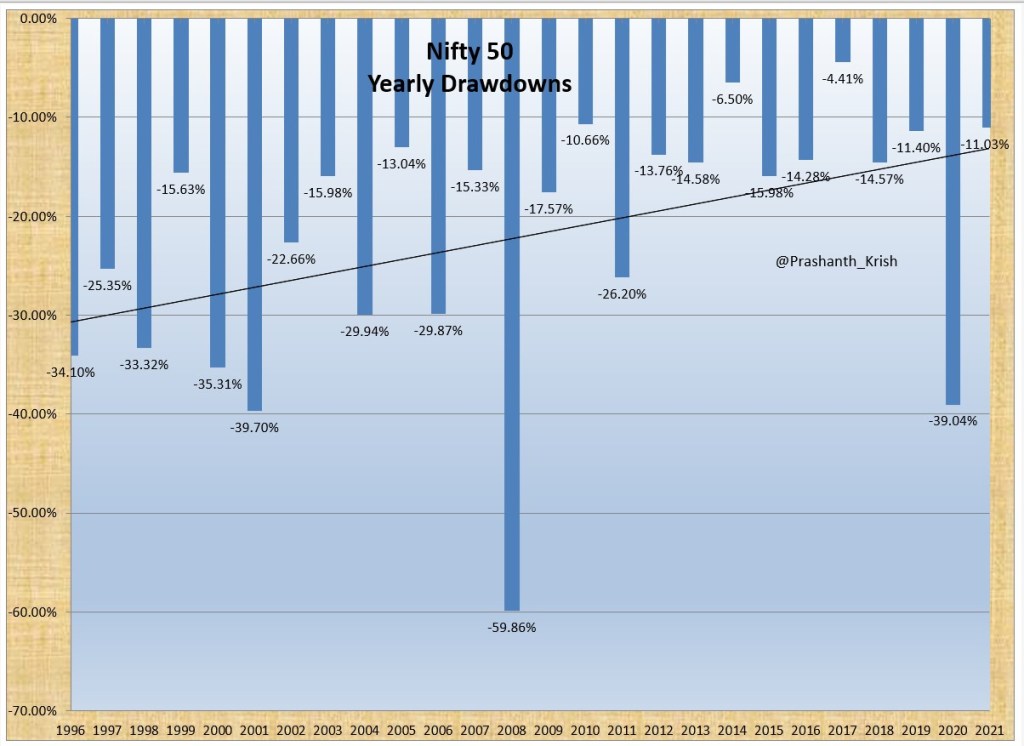

Markets go down every year. That is guaranteed. It’s more in some, less in others but on an average a 10% drawdown is guaranteed while even 20% is possible though in recent years we haven’t really seen one other than the Covid fall.

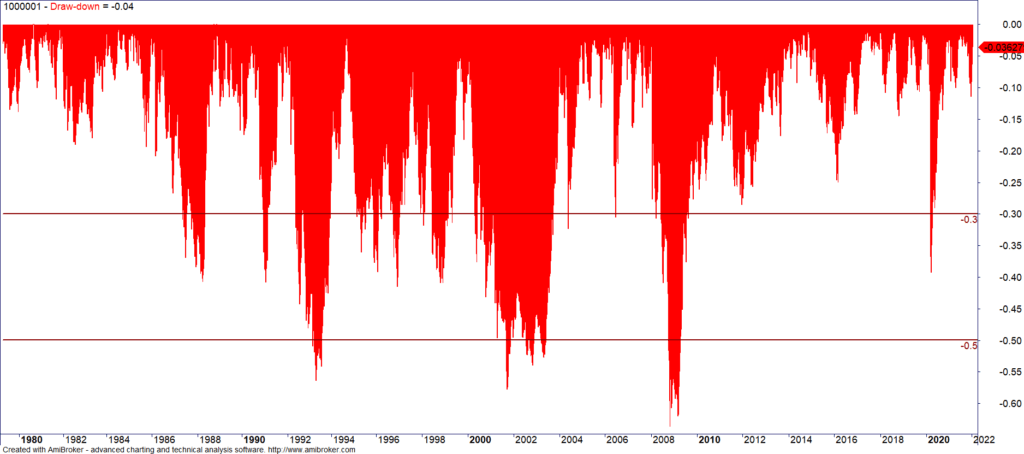

Look at the drawdown from all time high for the Sensex.

A 30% fall was normal pre-2008. 50% or more happened just twice. Things have changed a lot since 2008.

If you can have and really have and really live by a good long-term investment outlook, that will be close to an investment superpower as you will be ever able to achieve – Cliff Asness

Louis Simpson was one of the favorite fund managers for Warren Buffett. So good was he that if not for his age, he was seen as the person Warren would have been comfortable handing over Berkshire Hathaway post his own retirement.

In 1987, before the crash, he moved GEICO’s portfolio to approximately 50 percent in cash because he thought the valuation of the market was “outrageous. He was right and the market moved down 41% in the space of less than two months.

Simpson says that the huge cash position “helped us for a while and then it hurt us,” because “we probably didn’t get back into the market as fast as we could have.”

The key to success in avoiding a drawdown and benefiting from it lies being right twice – once when getting out and then when getting back in.

Everyone of us would love to be out when a drawdown hits and back in when the trend returns again. While advisors claim this is possible, I have for once not found a single PMS (where you can actually go to 100% cash as and when you feel like) ever talking about having either done that or this being part of their strategy.

The reason is simple – there are way more tradeoffs that one bargains for when trying to move to cash and back. First and foremost, the fact is that not every dip will result in a large crash making the move worthwhile.

The best strategy is one where you get out right before a big fall and get in before it starts to rise again. Other than in hindsight, you can never be right in such a manner. In almost any strategy, you shall get out once the trend has started to become bearish and re-enter when the trend has started to become bullish.

To better understand, we will need to look at what kind of strategy can get us out before big crashes and get back in post the event while also being mindful about not getting in and out one time too many.

Let’s take the 200 day EMA and assume one shall get out every time Nifty goes below this and gets back in when it goes back up. This strategy for instance would have kept you out of the Covid Crash of March 2020.

Even in 2008, while the strategy did not get out cleanly and stay out, it would have still saved a ton of money. In 2009, it went long just before the markets shot up 20% in a single day on the back of the election of the second UPA government. What more could you really ask for?

Nothing comes for free and even here there are some downsides.

The best way to compare a strategy is to compare it with a strategy that does nothing – in other words a Buy and Hold.

If you implemented the strategy – getting out when you were told so and got back in versus your friend who is a buy and hold investor who invested the same amount in Nifty in 1992, today your friend’s equity will be higher than what you would have had. In other words, your friend would be richer than what you are today even though both of you had invested in the same underlying index.

On the other hand, during the worst times, you were sitting pretty in Cash while your friend would have been aghast at seeing how much money was lost in such a short time. Most investors give up at the worst possible times. Having a strategy even as dumb as a 200 EMA cross minimizes that risk.

The second and bigger trade off is with the ability to stick to the strategy. Remember, your friend has to act only once and he is done. For you, it’s different. Since 1992, you would have entered and exited Nifty an additional 110 times. That is more or less 5 to 6 times a year. What is worse is that 75% of those trades lost money.

Finally, let’s assume that the investment is your life savings in its entirety. The larger it gets, the tougher it always is to get out when the markets are falling and even tougher to buy it back at a loss at a higher price. Not to mention the taxes to pay and the charges you end up paying. Life ain’t easy.

If you wish to reduce the frequency of trade, you can move to a higher time frame with a similar strategy such as the 10 month moving average. Meb Faber has written a bit about the said strategy here Timing Model – Meb Faber Research – Stock Market and Investing Blog

While the number of trades reduces a bit, the outcome isn’t too different. You still would have underperformed your friend. Of course, if you calculated this not when the markets are high but when the markets are at its low, you would have seen yourself as a winner.

The other day, I was listening to an interview of Bill Miller, the famed Value Investor and his thoughts on Volatility seemed interesting.

Achieving lower volatility than the average or achieving low volatility is not the objective of investing. It might be a psychological objective for people because their psyche’s don’t like to see them losing money because the coefficient of loss is two to one. But the objective is to make money and outperform the markets.

There is no escape from Drawdown regardless of the strategy. Charlie Munger in 1973 was running a partnership which saw a drawdown of 53% vs Dow’s drawdown of 33% for the Dow. While the intrinsic value of his holdings were definitely higher, the problem is always about not what it’s worth but what the market values it at.

Risk Tolerance & Asset Allocation

The other day I was listening to a very well known and accomplished person in the world of finance. He talked about how when markets fell in March of 2020, his system told him that it’s time to move 20% from Debt to Equity. He ended up moving 2%.

The pain of buying equities when the whole world seems to be selling is way too great to overcome even if we somehow have overcome that pain by selling after the markets have gone down from their highest point.

This is also one reason that binary systems which move from 100% Cash / Debt funds to 100% Equity (Dual Momentum for example) have so few takers despite tons of data on the benefits of following one such strategy. In fact, beating the underlying such as Nifty becomes possible in a Dual Momentum strategy if you were to move to say Gold vs Cash but who in their right mind can be 100% invested in Gold at any point of time?

Assume you own a portfolio worth a Crore of Rupees and as of today that is all you have. Markets start to fall but your system is still telling you to stay being long equities. You are uncomfortable but you are intelligent enough to know that the system is always right and you are better off sticking to it.

Market falls even more and finally your system says – Sell everything, move to Cash. Depending upon your own predisposition, the probability is that you will do exactly as the system said, more so if the day post the signal gets generated is a negative day.

Post your sell decision, the market starts to seemingly flatten out but we are now hit by a wave of bad news, news that was most probably the reason why markets fell in the first place. You start to think that you did the right thing by getting out for who knows how deep the markets can go down.

But a few days later, the market starts to climb. You ignore this as part and parcel of the gyrations that one will see in such times. A few more weeks later the market is higher, higher than where you sold. You would feel bad but still believe your call to exit was the right one. Two days later, the news is as bad as it was at the bottom but markets have moved up 15% from the lows and 10% from where you sold and your system signals a Buy.

Would you turn around, sell all the Debt Funds / use the Cash and buy back 100% of the equity you sold?

The probability of one doing it is low and this is how the majority will actually react. It doesn’t matter how much experience one has, the probability is always low, more so if one already has had seen a couple of whips.

Why this dichotomy between the decision to sell and buy?

The answer lies in the fact that when we lose money, even notionally, we suffer pain. Pain is so great that we are happy to unload the position even at a substantial loss. But buying again is tough because our recency bias tends to reflect upon the recent bad news with expectation of failing once again. Why get back so soon, should not the news settle down is a much asked question during these times.

One reason investors choose the Do it yourself approach especially when it comes to stocks is the control one has over the construction of one’s portfolio. An added benefit is of course that there is no fee you would pay.

Do-it-yourself also means a low or flat fee at best. On the other hand, the fee we pay is not in terms of money but in terms of being able to mold our psychology and be prepared to continue with our journey in both good days and bad.

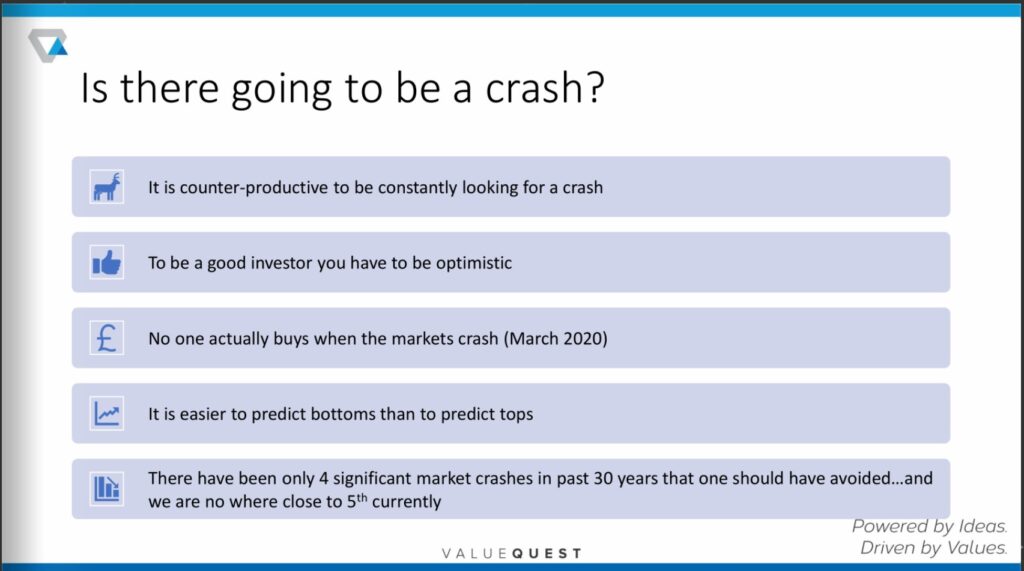

Finally a slide from Ravi Dharamshi of Value Quest Advisors. Key point is the last point – 4 big crashes out of 30 years that should be avoided.

4 in 30 years is close to one in 7.5 years. Trying to get in and get out wondering if this fall is going to be the 5th will in the long run turn out to be more expensive than staying put and sailing through the rough waters.

Book Review: Damn Right!: Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger

It’s always fascinating to read about great investors and who is better than Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. But unlike other investors, it’s tough for neither have written a book themselves or are there any authorized biographies.

Warren Buffett’s rise is more of an open book. Charlie Munger on the other hand is much more subdued.

This book can be said to be kind of the closest one can get to a Charlie Munger Biography. It doesn’t pack the wit and wisdom which one can gain by reading Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger and Seeking Wisdom – From Darwin to Munger

Instead this book looks at Munger with focus more on his family and his the path he took before he joined Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway.

While compounding may be the 8th wonder of the world as Albert Einstein once put it, compounding from a small base doesn’t really place one in the Forbes list of the richest folks in the country.

Warren Buffett’s path is well known as to how he came to accumulate enough capital. Charlie Munger on the other hand isn’t that well known. For me at least it was a surprise to learn that Charlie made his first Million in real estate deals.

Compared to Warren, Charlie comes off as a risk taker. His real estate deals as well as a couple of stock acquisitions were leveraged to some extent. Of course, his bigger risks were career related, taken at a time when he had a large and growing family.

While much of the talk is about the folksy way with which the two went to town acquiring good business at reasonable prices, this book and the one I read before – Capital Allocation: The Financials of a New England Textile Mill 1955 – 1985 showcases that it wasn’t such straight forward, especially in the early days. They were able to acquire good companies but were going through their own difficulties.

The biggest advantage Munger and Buffett had during their early years was the fact that they matured during a period when the market went nowhere for a decade and more, providing them not just the opportunities but also showcasing the advantage of patience.

Today with blank check companies raising billions, the edge has receded a lot for anyone who wants to follow a similar path. While we may never be able to replicate the path the pioneers take, reading provides a framework of what can be applied to areas that are different and yet similar to Value Investing.

If you are a fan of Munger and wish to read more about his life and family, this is a book for you, else one can give this a pass.

Good

I understand the problem because I have faced it. But even after reading your blog I couldn’t see a solution, how do u suggest we overcome it?